My first month or so at the Museum has been spent cataloging donations of player piano rolls, sheet music and records. Almost all the recorded materials we took on were made by and for Arabs in the U.S. and overseas. The sheet music collection, however, hails primarily from America’s Tin Pan Alley, a handful of music publishing houses in the early 1900s that grew in popularity during the height of vaudeville. While these objects represent the evolution of recorded music, they also reveal a story of how diasporic communities used music to create space for themselves in the U.S. and contrasts that narrative with American perceptions of Arabs that were being formed in the early twentieth century.

From the late 1800s into the 1920s, migrants from the Arab world began carving out enclaves in cities across the country. This timeline coincides with what some consider to be America’s golden age of songwriting. In an era before recorded sound, vaudeville style variety shows were the engine of American pop music. The sketch-style nature of these shows only gave performers a handful of minutes on stage, and so racial or cultural stereotypes were often used to convey a message to the audience in the shortest amount of time possible. While there were some acts involving stereotypical Irish or German characters, a vast majority of the harm fell onto communities of color.

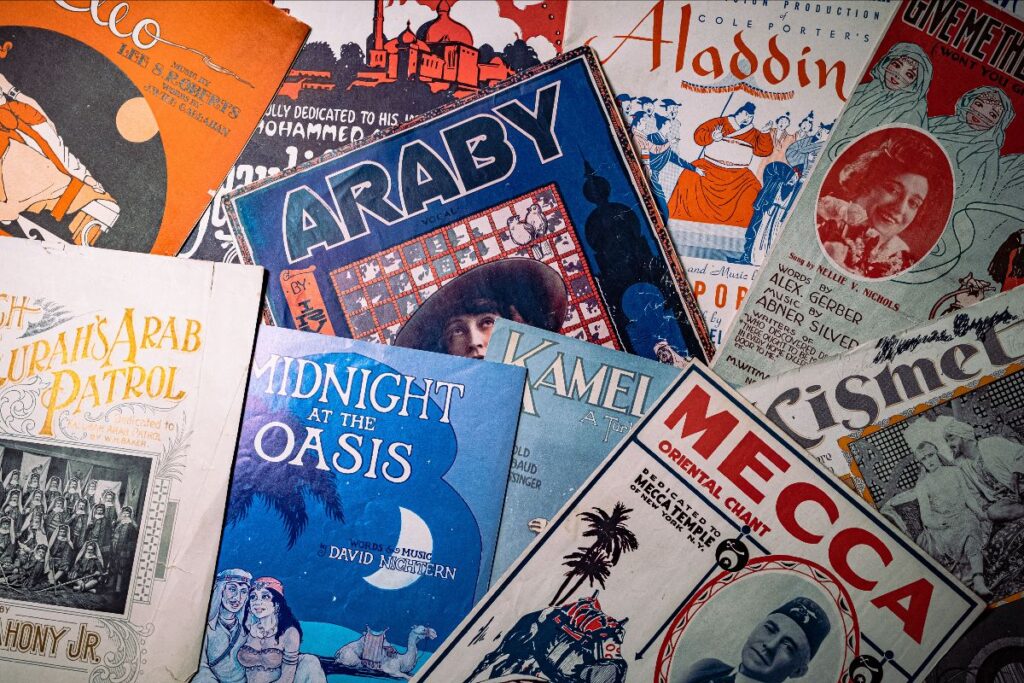

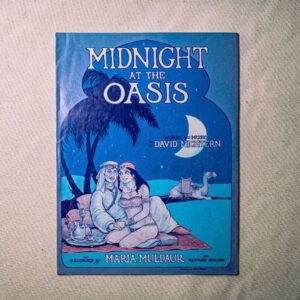

As news of World War I entered the U.S., so did Orientalist ideas about the people and cultures being encountered by Westerners. Many song titles and lyrics found in the collection we received feature stereotypical images of camels, sheikhs and harem-bound women—what else can one expect from the same genre that produced the blackface character Jim Crow? Despite its racist tropes, the music of the era has unbelievable staying power, as do the caricatures and stereotypes that have become synonymous with the vaudeville genre.

As news of World War I entered the U.S., so did Orientalist ideas about the people and cultures being encountered by Westerners. Many song titles and lyrics found in the collection we received feature stereotypical images of camels, sheikhs and harem-bound women—what else can one expect from the same genre that produced the blackface character Jim Crow? Despite its racist tropes, the music of the era has unbelievable staying power, as do the caricatures and stereotypes that have become synonymous with the vaudeville genre.

Moving to a new place where no one knows your name—let alone the culture or country you come from—can be, to put it lightly, daunting. Nevertheless, across different cultures, immigrants found ways back to each other as they built new lives in the United States, much like we see in Manhattan’s Little Syria. Music was just one avenue of connection, but it is arguably one of the most powerful. It gave people a reason to gather and provided means for community building in a new country. With the invention of the phonograph and subsequent audio recording technology, swelling strings, lilting ney and pensive oud could now be scored onto ceramic discs and packed away in steamer trunks only to be played again in moments of homesickness. Once the needle dropped, the village became tangible, and suddenly a city that felt foreign was flooded with something more familiar.

As the Arab community continued to grow in the U.S., so too did the market for Arabic language music. Abraham Joseph (A.J.) Macksoud was just one of the many people who rose to meet this need with a phonograph store in Little Syria. Many of the records AANM acquired this year feature a small, circular sticker with Macksoud’s name and store address on 89 Washington Street, one of the vibrant thoroughfares of Little Syria. More entrepreneurs, like Farid Alam of Alamphon, would follow Macksoud’s example.

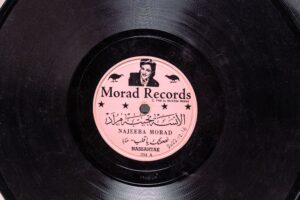

Perhaps no other piece in the collection exemplifies the “by, of, and for us” energy than one from Najeeba Morad, the Daughter of the Mahrajan. Morad was an incredibly popular singer who performed live at haflas and mahrajans across the United States. Her appearance at the anniversary of the Syrian American Club of Boston in 1933 earned her the nickname the “Syrian Nightingale.” While she was most well known for her live performances, Morad must have recorded songs at some point in her career as evidenced by a couple of albums from Morad Records that the Museum now has in its collection. Even though it must have been produced by a professional press, something about the pale pink label with simple black text feels homemade. Listen to a recording of Najeeba Morad here.

Morad’s promotional photo sits squarely at the center flanked on either side by black birds, perhaps a reference to her aforementioned title. Morad performed well into the 1980s. Her success, as well as the success of many other Arab American musicians and performers, is a testament to the power music holds in community building. Her career was not dependent on Western audiences or their perceptions of Arabs—she was an Arab American performing music for Arab American audiences. Alongside stories of Najeeba Morad and the homegrown Macksoud Records, the Arab American National Museum is excited to explore and elevate the stories within these musical collections.

Dean Nasreddine

Dean Nasreddine

Curatorial Specialist

Arab American National Museum