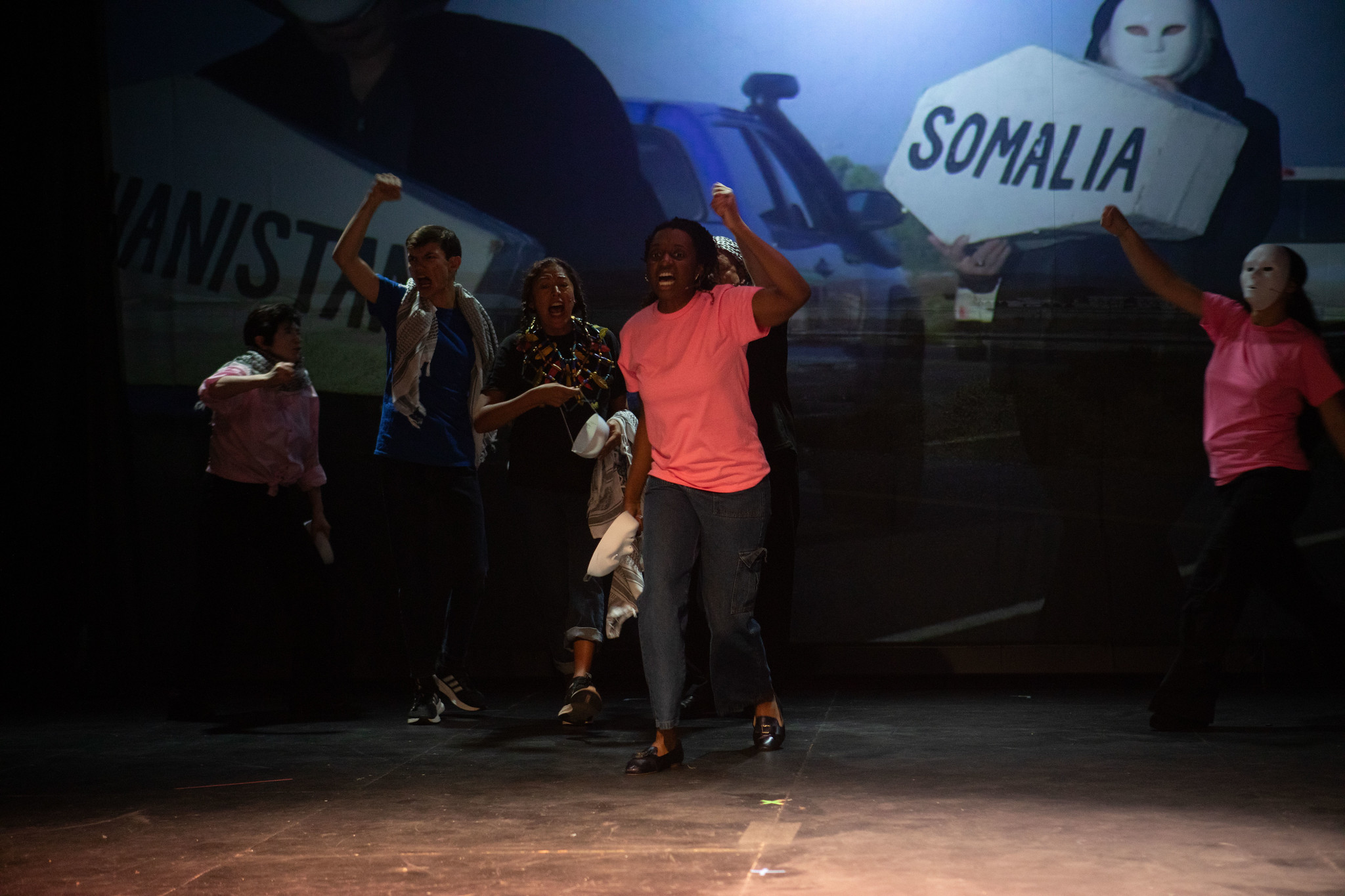

DRONE: A New Play by Andrea Assaf performed at the Detroit Public Theater from July 31 - August 3. Find upcoming AANM events on our calendar.

DRONE, written by Joyce Award-winning playwright Andrea Assaf, is a heart-gripping play about a pilot who lands a well-paying job as a military contractor flying drones, and the mental health struggles that follow after a drone attack with civilian casualties.

The play begins on a hopeful note: commercial pilot Ryan Byrne is happy to start a new, financially stable life with his wife, Maggie, and son, Buddy. He sets off to work at Creech Air Force Base. We learn that he doesn't fully understand what he's getting into until it's too late.

During a drone operation, the squad at Creech realizes they’ve accidentally targeted and killed civilians in a small, Middle Eastern village. Ryan is immediately distraught. While he didn’t physically fly the plane and drop the bombs, he still feels responsible for the remote decision.

He confides in The General, a Vietnam-era Air Force veteran who believes drones are an incredible military advancement, as American troops can now carry out orders without having to risk their lives in the field like he did. We learn some horrific details about his experiences in battle and empathize with his perspective. And yet, his perspective doesn’t account for the loss of innocent lives in faraway countries, and the ease with which they can be taken.

Three Survivors visit Ryan and haunt him with their testimonies of loss and pain. He becomes distant and unpredictable with his family, and his mental health worsens. Maggie reaches out to a local church for help, which only makes her feel more trapped in her marriage to a man who is quickly losing his grasp on reality.

The play is set in Las Vegas. Yes, there is a casino scene, and not just one but several Elvis impersonators, much needed comic relief. One of the most enjoyable scenes is when one of the Elvis Impersonators turns out to be the Preacher at Maggie’s new church and breaks out into song.

Speaking of priests, religion serves as a strong subplot. The play touches on a far-right Christianity that connects the wars in the Middle East to the Second Coming of Christ. It also features the ancient Egyptian goddess Sekhmet, and the Muslim women Survivors, a nod to Muslim majority countries that are currently targeted by the U.S.

Finally, the music, an experimental mix of Christian hymns with Middle Eastern music, is nothing short of incredible. The ensemble features internationally acclaimed, Dearborn-based artist, Lubana al-Quntar, an opera singer from Syria. And Kathy Randels, a theater director, vocalist, and performance artist, who showcased her extensive knowledge of U.S. Southern and Appalachian Christian music. They play in front of a projector, which makes for an immersive, interactive experience that pulls you in.

Survivor testimonies and a veteran’s moral injury highlight character complexity.

There are two narratives at work in DRONE, and they interject a layered interpretation of story lines many American audiences are familiar with: the solider and the survivors.

It was crucial to Assaf to avoid depicting tired tropes around victimhood. We learn that The Survivors that visit Ryan are three Muslim women from different countries, based on actual, real testimonies of witnesses and survivors of U.S. drone strikes in Yemen, Pakistan, and Somalia. By using real testimonies, Assaf amplifies the powerful effect of lived experiences.

“I call them ‘The Survivors’ because, while their communities have been victimized, they are people who speak out and demand change,” Assaf said. “It was important to me that they are seen as women who have agency in their stories.”

While The Survivors are fictionalized, Assaf re-wrote much of the real testimonies into multi-voice poetry. The Survivors speak in fragments and complete each other's thoughts and sentences. They don’t seem to know the others exist, and yet the audience experiences them together as a single unit. The testimonies set to poetry makes for a moving presentation that is both mesmerizing and difficult to witness.

“I was interested in the chorus in a classical tragedy, and what that might look like in contemporary spoken word,” Assaf explained. “And I was interested in how these witnesses in completely different countries and contexts, who have never met each other or heard each other's words, say the same words when they describe what they’ve seen. I wanted to really highlight the symbiotic nature of their stories interwoven by shared trauma.”

Assaf also wanted to create a pilot who wasn’t a cold-blooded war machine. She created an everyday person who is just trying to live the American dream and support their family. His job is to kill people though, and the way he does it—via remote technology—feels cold, empty, and removed. It makes him question his place in time and reality.

Around the same time Assaf was writing the script for DRONE, she was leading theater workshops in Florida at a recovery center for U.S. military veterans. She was also directing another play, Speed Killed My Cousin by Linda Paris Bailey, about a woman who comes back after serving in the Iraq War and battles suicidal ideation. It was during this work that Assaf really learned about PTSD and Moral Injury in Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Gulf War veterans.

Why did many of them come back with a desire to commit suicide, she wanted to know. “Usually, it's because they know things about what we've done in wars that are not public knowledge, and that in some cases the soldiers aren’t allowed to speak about,” she said.

“Moral Injury” is the cognitive dissonance created when you do something that is against your own personal moral code.

“The easiest way to think about it is that PTSD is about something that you went through or that happened to you. Moral injury is about what you did or didn't do,” Assaf said.

A few times, Assaf has accessed someone who's been part of the U.S. drone program, which is challenging because they're not allowed to discuss it with others. Those who do speak out do so as activists. What's interesting, Assaf notes, is that drone pilots often aren't eligible for PTSD services through the VA, because from the government's point of view they were never physically in combat or exposed to danger. As she learned from therapist and former VA professional Dr. Lynne A. Santiago (LMHC), PTSD isn't necessarily a driver of suicide, but Moral Injury is.

“Did you know during the Iraq War, there were more veterans who died by suicide than by a combat?” Assaf asked. “And that statistic includes Vietnam vets who are still living with the impacts of Moral Injury 30 to 40 years later.”

Research has shown that crimes against humanity weigh on the human psyche over time. Moral Injury reaches beyond a diagnosis and explains what happens on the soul level to soldiers tasked with “protecting our freedoms.”

“Looking at Moral Injury is what really leads me to look at our military system and ask, ‘What is it that we're doing?’ It's the people most directly involved who on some level know they've been a part of something horribly wrong,” Assaf said.

Meet the playwright: Andrea Assaf discusses her journey in art and activism.

Andrea Assaf grew up between Washington, D.C., Maryland, and rural Pennsylvania. She decided very early on that theater was her calling and went to NYU to master her technique and craft.

It wasn’t until the 1990s, however, that Assaf felt ready to share her work. “I was always a writer, but my writing was private and personal,” she recalled. “Then I started to realize, oh, I could actually write and create my own work as a theater artist.”

Assaf’s earliest activism was during the AIDS Crisis, when she just started coming out as a queer artist. Her activism focused on AIDS education and LGBTQ+ rights. Then she joined protests around corporate globalization, the IMF, and World Bank, and how that was affecting economies all over the world. The tipping point for her, however, was 9/11/2001, when she was suddenly very aware of her identity.

“I was in New York. It changed my life forever, really,” she said. “I was an emerging artist who was just figuring out my voice.”

Assaf was immediately targeted as Middle Eastern or Arab, and people would assume she was Muslim, even though her family had always been Catholic (on both sides). Up to that point, she wasn't strongly Arab identified. She’s Lebanese American on her father's side, white American on her mother’s side, and didn't grow up with the Lebanese or Arab community.

While 9/11 was confusing and painful, it allowed Assaf to carve out her path as an artist.

“As a queer Arab woman, I experienced a lot of backlashes,” Assaf said. “That became a central focus of my work, which has mostly been about war and peace since then. My current project, DRONE, is the most recent iteration of that.”

How a Catholic priest’s arrest led to DRONE’s inception

In 2009, Assaf was driving in her car and listening to her favorite news program, Democracy Now! with Amy Goodman. She heard a story about a Catholic priest who protested outside of Creech Air Force Base in Nevada and was arrested. He was protesting drone warfare, which was just starting to gain national consciousness. The story resonated so much with Assaf that she went to the base and joined a week-long protest and vigil with Code Pink and Veterans for Peace in 2019.

Interesting fact: if you see the cover image of the play, there’s an image of a person wearing a white mask and a keffiyeh in the desert. It’s actually Assaf wearing the mask. She just happened to have a keffiyeh that day and used it to cover her mask. The irony is that now, in 2025, when we see a keffiyeh, we think of Gaza. And when we think of drone warfare, we also think of Gaza.

The mask was part of a funeral procession. The protestors wore masks and carried small coffins with names of countries where the U.S. had been conducting illegal drone strikes, such as Yemen, Pakistan, Somalia, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

Assaf reminds us that people either don’t know or tend to forget that the weaponization of drones are a George-W.-Bush-era program. Drones had already been in use for surveillance and reconnaissance by the U.S. military, Israeli military, and possibly others. But the U.S. began deploying them as military weapons in 2003.

“A lot of people highlight Obama's role in the drone program,” Assaf said. “While it escalated under him (which felt like a betrayal for many of us people of color in the United States), the weaponization of drones started early in the Iraq War.”

Meeting the biggest challenges head-on

It took 10 years for Assaf to get funding for DRONE, largely because of its political nature and critique of U.S. military policy. In 2019, she received support from the Arab American National Museum, the National Performance Network (NPN) Creation and Development Fund, and the New England Foundation for the Arts (NEFA) grant program, the National Theater Project. In 2024, she won a Joyce Award in partnership with the Arab American National Museum.

“I’m very, very grateful to the Arab American National Museum for being a strong supporter from the early stages until now,” Assaf said. “The support of the Joyce Foundation has also made this production possible. And the partnership of Detroit Public Theater is something I'm very excited about.”

Another obvious challenge is that the content is emotionally challenging. There are descriptions of war and death, domestic violence, and recounting of trauma. Assaf learned a lot about how to support actors in the process. And she even partnered with Kim Pevia, a Native American healing practitioner and facilitator, to help the team through such heavy topics.

Assaf was also mindful of audience reactions. The play’s first full performance was at the Detroit Theater where many attendees were Middle Eastern and other people of color. She encouraged attendees to take care of themselves in between heavier scenes if needed. Assaf knew that what she was asking us to watch would, and it did have a profound effect on its viewers.

“This play asks us to wrestle with our complicity as American citizens, or even residents or immigrants who pay taxes to the U.S. military industrial complex,” she said. “It’s hard to sit with. It's hard to face. But it's like the old adage: nothing can be changed until it is faced. The play is asking us to look at the impacts of the drone program from all sides.”

Creative uses of technology versus weaponization

Assaf incorporated high tech and emerging technology such as live feed and motion tracking cameras. She wanted to create an environment that helps us distinguish between and interrogate tech that inspires and empowers us, versus that which can be used as a weapon.

“As soon as you start weaponizing technology, it becomes very dystopic,” Assaf said. “It's interesting because in theater, when you write drama or tragedy, there's a fatal flaw the main character has that propels the drama into tragedy. Technology can have fatal flaws, too, but in that case, it's literally fatal…For example, a small glitch in an AI technology could be catastrophic.”

So, how do we distinguish between helpful, positive tech and the destructive, world-ending kind?

“We are early enough in the process to stop that destructive path from happening,” Assaf said. “In other words, if we get people to care about policies around the use of drones and drone warfare, if we have ethical conversations, if we're willing to say no and not vote for people who will support the weaponization of drones or the progression of AI in warfare, it might still be possible to get it under control. But if we don't engage, talk about it, care, or speak up, we're headed toward a dystopic path.”

Advice for other writers and artists

Assaf has advice for those who are creating and paving their own path during war, civil unrest, and tragedy. She encourages artists to make their own work and be true to their voice, particularly those who are often marginalized. “If we as people of color, Arab Americans, queer artists, etc., try to fit into the systems that exist, we often shrink our own voices,” she said.

“The only way to be fully who you are is to make your own work,” Assaf said. “And that means finding the partners who believe in it with you, and help you achieve a vision. And sometimes it means raising your own money, producing your own work, and doing all the organizing and administration, which is not all the fun part. But if it gives you autonomy and agency, and allows you to resist censorship, then I encourage you to keep going.”

Assaf is proof that resistance is a long but worthwhile road. As someone who has been protesting since the 1990s, it’s amazing to witness someone who has not given up hope on future possibilities.

“I think if the movement for Palestine is teaching us anything right now, it’s that the truth will always come out, and the truth will win. It might be a long road,” Assaf said. “Like Dr. Martin Luther King said, ‘The arc of history is long, but it bends toward justice.’ We have to believe in that.”