Header image: An ad for al-Rabita appearing in the 1930 Syrian American almanac.

Al-Rabita Al-Qalamiyya (The Pen League): A Digital Exhibition

Research Manager Matthew Jaber Stiffler and Curator of Exhibits Elizabeth Barrett Sullivan introduce this online exhibition.

Introductory Essay by Janna Aladdin, PhD student in Modern Middle East and Islamic History

Fueled by their interests in mysticism, philosophy and spirituality, members of al-Rabita collectively formed the mahjar (diaspora) school that aspired to rethink the form and essence of Arabic literature and language. Their animated literary and artistic world created a home in New York from where they could withstand the potentially pernicious effects of ta’amruk, or Americanization. On the hundredth anniversary of al-Rabita’s establishment in 1920, al-Rabita al-Qalimiyya: A Digital Exhibition presents a range of images and texts including poetry books, articles, personal letters and community journals published and written by the League’s members. By presenting a small part of the members’ archives, this exhibition offers a glimpse into al-Rabita’s vibrant worlds and ambitious undertakings.

Janna Aladdin is a graduate of the MA program at NYU’s Kevorkian Center in Near Eastern studies, where she studied Arab intellectual, religious and legal history and Arabic literature. She was a 2016-2017 Center for Arabic Study Abroad (CASA) fellow in Amman, Jordan.

In 1921, Lebanese poet and novelist Mikhail Naimy presented an anthology of Arabic short stories, poems and articles written by members of al-Rabita al-Qalamiyya (The Pen League). Evoking the League’s principles, Naimy wrote in his introduction: “The Pen League would not present this collection to readers of Arabic, were it not convinced that it makes literature into a messenger and not simply as an exhibition of linguistic style or prosodic frippery.”1 Literature, Naimy argued, served as a messenger between the writer’s soul and the soul of others, revealing the depths and multitudes of one’s inner self. Naimy was joined by such figures as Kahlil Gibran, Ameen Rihani, Nasib Arida, Rashid Ayyoub, Wadi Bahout, William Catzeflis, Abd al-Masih Haddad, Nadra Haddad and Elia Abu Madi in convening the League’s literary salons, based in what was known as the ‘Little Syria’ neighborhood in Manhattan, and in channeling literature’s transformative and creative energies. Fueled by their interests in mysticism, philosophy and spirituality, members of al-Rabita collectively formed the mahjar (diaspora) school that aspired to rethink the form and essence of Arabic literature and language. Their animated literary and artistic world created a home in New York from where they could withstand the potentially pernicious effects of ta’amruk, or Americanization. On the hundredth anniversary of al-Rabita’s establishment in 1920, al-Rabita al-Qalimiyya: A Digital Exhibition presents a range of images and texts including poetry books, articles, personal letters and community journals published and written by the League’s members. By presenting a small part of the members’ archives, this exhibition offers a glimpse into al-Rabita’s vibrant worlds and ambitious undertakings.

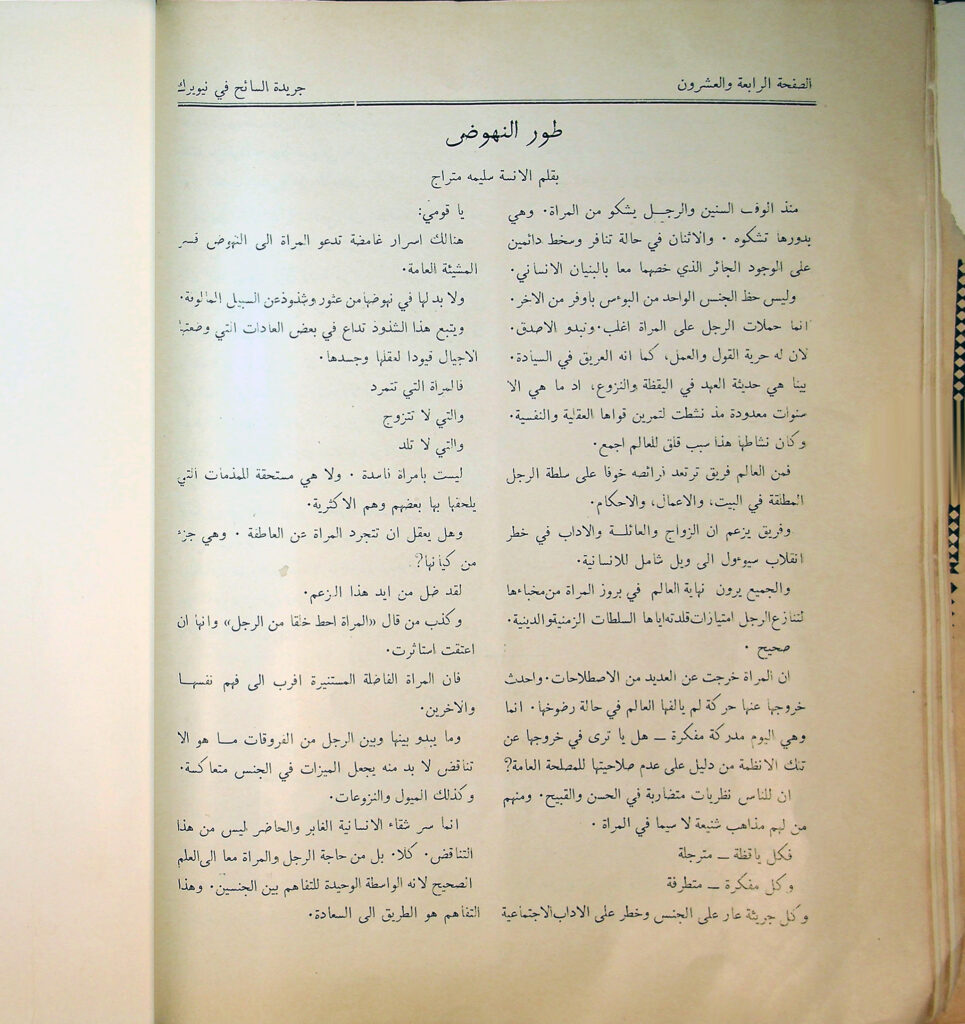

Members of the Pen League arrived in the United States in the late 1800s and, like many Arab immigrants, they left behind economic and political hardships. During this first period of Arab migration to the United States (1880s–1924), al-Nahda al-‘Arabiyya (generally translated into “Arab Renaissance”) — an era marked by vast literary, linguistic, cultural and political transformations — was underway across the Arabic-speaking world. Figures like Naimy, Gibran and Rihani expanded the geographic scope of the Nahda by submitting articles and stories to Arabic journals including al-Muqtataf, published first in Beirut then in Cairo. Kahlil Gibran’s article “The Future of the Arabic Language,” for example, partook in Nahda-era debates about language. In the article, Gibran extols the virtue of the Arabic language while urging for linguistic and literary innovations as a sort of awakening, away from the ‘prison’ of imitation and traditions. Most of these publications including al-Funoon – some of which are part of this exhibition – were printed by Arab American publishers, such as Salloum Mokarzel, eager to introduce new printing techniques and improvements to the Arabic linotype. Even with the technical (and mechanical) advancement of Arab American publishing, minor issues emerged; punctuation was often printed incorrectly, such as question marks that faced left (which is the wrong direction in an Arabic text). Perhaps the inverted question mark can represent the members’ main concern looming in the background: a sense of disorientation and alienation from their home countries and losing their identity and culture as a result. Yet certain opportunities and new expectations exist in the borderland between emigration and immigration: the possibilities to conceive of Arab culture and identity anew and to bring the Arabic-speaking world to the United States. For instance, Rihani brought Syria and Cairo to New York by publishing poems in The Atlantic, Poet-Lore, Harper’s Magazine and The Bookman including his poem Hanem, in which his lover in Cairo asks the well-rehearsed diasporic question, “When shall we, Syrian, meet again?” Immigration also produced new financial and practical concerns as well. Attempting to serve the growing Arab community in New York, the League organized a series of classes on etiquette needed in American society. Periodicals such as the Syrian American Commercial Magazine advertised a wide range of merchandise and imports along with immigration and translation services as well as a section on news from the Arab world.

The Pen League eventually dissolved following Naimy’s return to Lebanon and Gibran’s death in 1931, leaving behind one of the most important archives in Arab American and Arab diasporic histories. The League’s legacy has proven resilient and its afterlives are carried in the many statues, collections, events and museums, as well as this exhibition, dedicated to its history and contributions.

1 Translation is Janna Aladdin's own.

Diana Abu-Jaber, PhD reads “On Love” from The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran.

Click the images to learn more and to read the complete books

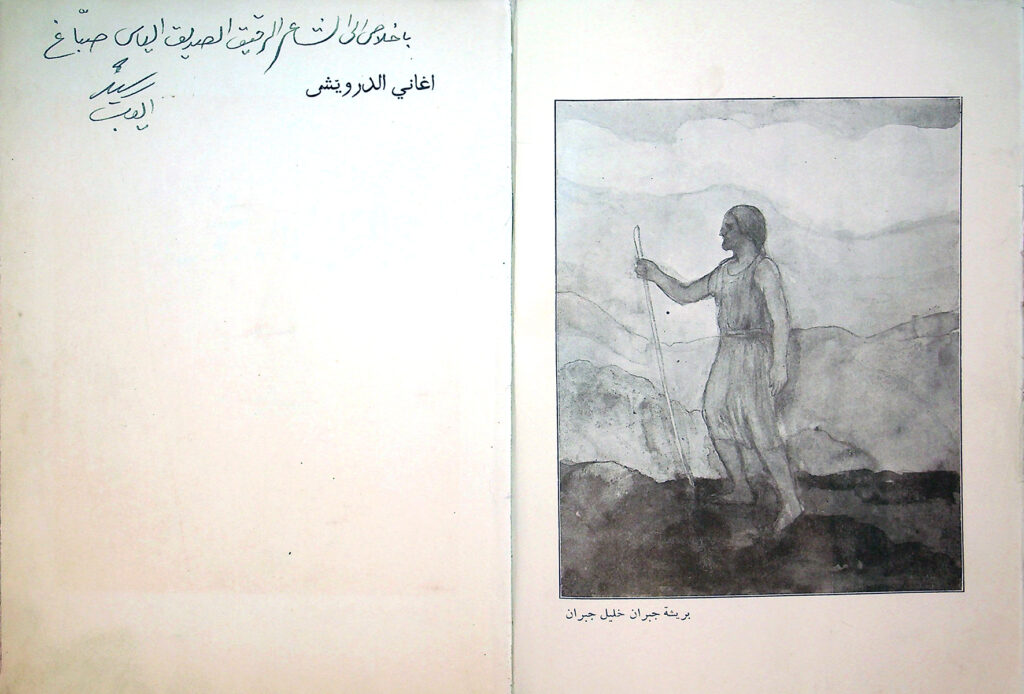

First edition of The Prophet inscribed by Kahlil Gibran to Naoum Mokarzel, owner of the newspaper Al-Hoda.

Cedar branch from the Lebanese Government that hung in the Al-Hoda offices, ca. 1930s. Gift of Helen Samhan and the University of Minnesota Immigration History Research Center.

Omar Offendum performs “Dead Are My People”, a poem by Kahlil Gibran in response to the famine after World War I. AANM owns a letter by Gibran to the President of the Syrian American Club of Boston.

Carol W. N. Fadda, PhD, reads an excerpt from “Does a Homemaker Deserve a Salary?” by Victoria Tannous. Tannous is included here as women would have been excluded from al-Rabita at the time. She and other female writers contributed greatly to Arab American literature and journalism.

Khaled Mattawa, PhD, reads an original English translation of “al-Masaa” (“The Evening”) by Elia Abu Madi.

Sinan Antoon, PhD, reads an Arabic translation of “The Revolution” by Ameen Rihani. This poem was originally written in English in 1907.

View more of AANM’s al-Rabita al-Qalamiyya items in our online collections databases through the links below:

Selected full texts and documents

Community efforts in New York City to preserve the legacy of al-Rabita writers